My father did not tell me much about his childhood. And I, by stupidity, was not very interested in the details of his life … He seemed huge, severe, I saw him a little, he went out in the dark, came for a short time – in huge rubber boots, a hoodie and a whip. I was afraid of him. My father was a collective farm agronomist and was driving around the fields of villages. All of them were in the Orhei district.

On May, 21 he would be 110. Of the major events of the twentieth century only the collapse of the USSR did not happen during his life.

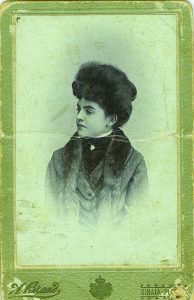

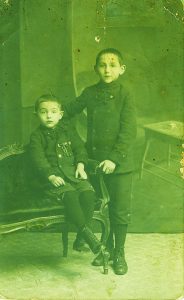

The boy Maurice, the first-born in the Romanian town of Braila at the family of Froim Braunstein and his wife, the beautiful Ernestina, nee Bernfeld, was born in 1907. In 1910, another young boy, Wilhelm, was born. In the same year their father, my grandfather, died. Mother after some time married again. Children lived – alternately – at different relatives, in Braila, in Ploiesti, then in Bucharest. Once, when my father and I were in Bucharest, I showed him the locked one synagogue I had visited the day before. He told me that he had been there with my grandfather when I was a child. It was a Sephardic synagogue. Father told how he remembered the black suits of men like from the 16th century, their appeal to each other “Don” and the Spanish speech. So the father called, for simplicity, Sephardic, Ladino.

The boy Maurice, the first-born in the Romanian town of Braila at the family of Froim Braunstein and his wife, the beautiful Ernestina, nee Bernfeld, was born in 1907. In 1910, another young boy, Wilhelm, was born. In the same year their father, my grandfather, died. Mother after some time married again. Children lived – alternately – at different relatives, in Braila, in Ploiesti, then in Bucharest. Once, when my father and I were in Bucharest, I showed him the locked one synagogue I had visited the day before. He told me that he had been there with my grandfather when I was a child. It was a Sephardic synagogue. Father told how he remembered the black suits of men like from the 16th century, their appeal to each other “Don” and the Spanish speech. So the father called, for simplicity, Sephardic, Ladino.

Since my father’s stories were sketchy, he sometimes recalled one or another episode, I will try and reproduce some of his memories.

Since my father’s stories were sketchy, he sometimes recalled one or another episode, I will try and reproduce some of his memories.

I remember how in the late 50’s parents went to Chisinau, to the theater, most likely, it was just opened “Luchafarul”, with the troupe who had just been educated in Moscow. My mother and father returned, joyful, excited, constantly talking about something. The performance was based on a play of the Romanian writer Mikhail Sebastian “The Nameless Star”. Many years later, when we were in Bucharest, my father told me that Joseph Gekhter (the real name of Sebastian) was a friend of his childhood and, for a while, a classmate. My father told me this, going to another childhood friend, Elli Roman, the author of the Romanian hits which was broadcasted almost daily by the Bucharest radio. He returned from him in a very depressed state, said that Elli was seriously ill. He lay down, turned to the wall, and for a long time was silent, exactly the same as 20 years before when he received a message from Paris that his uncle, Marcel, who helped him with the payment of his studies had died. My father graduated from the Faculty of Agronomy at the University of Nancy. Elli, by the way, survived my father for eight years…

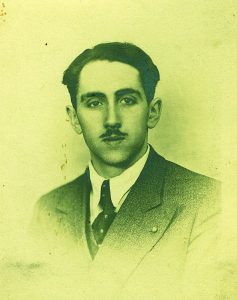

As a child, I perceived the profession of the father as a given, not reflecting why a Bucharest teen, who had nothing to do with agriculture, had suddenly gone to study in France, for an agronomist, and why he immediately found himself in Palestine upon receipt of the diploma. Over time, everything was arranged in a harmonious picture: the father’s stories about how they studied jiu-jitsu, walked with brass knuckles with his friends – most likely they were in the then created in Romania department of Beitar, and the subsequent study on the agronomist, after which he went on a steamboat, carrying cattle to Haifa, and living in a tent, and working on an orange plantation. The father consciously wished to participate in the construction of what soon became Israel.

It so happened that after living a year and a half in Palestine, he was forced to come to Bucharest, his mother fell seriously ill. It was not possible to return Back to Palestine. The British did not give a visa. Thus, he became one of seven Jewish agronomists in Romania. He became manager of the estates of a Romanian aristocrat, Count Konstantin Kosta-Foro. He was a man of progressive views who fought anti-Semitism in Romania. He was one of the founders and secretary of the Romanian League for Human Rights. For the publication, in French, of the pamphlet “La Roumanie et ses prisons” – “Romania and its prisoners” – the Syndicate of Bucharest journalists excluded the count from its ranks.

It so happened that after living a year and a half in Palestine, he was forced to come to Bucharest, his mother fell seriously ill. It was not possible to return Back to Palestine. The British did not give a visa. Thus, he became one of seven Jewish agronomists in Romania. He became manager of the estates of a Romanian aristocrat, Count Konstantin Kosta-Foro. He was a man of progressive views who fought anti-Semitism in Romania. He was one of the founders and secretary of the Romanian League for Human Rights. For the publication, in French, of the pamphlet “La Roumanie et ses prisons” – “Romania and its prisoners” – the Syndicate of Bucharest journalists excluded the count from its ranks.

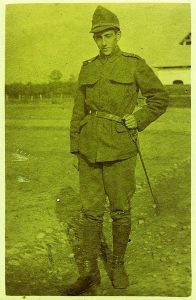

In June 1940 the successful Romanian agronomic career was abruptly cut short. My father was at military trainings in Tulce, near the unexpectedly formed new border with the USSR. The commander of the regiment for a given bribe gave the Jewish sergeant a firing note. I do not have details of how the father met his first wife to cross the border, and how they crossed it. Obviously – on foot, on the bridge over Prut, in Reni. Further, the father turned out to be a German spy (!!!) in Balti. Naturally, in the NKVD. Naturally, not knowing a word in Russian. He spent a couple of interesting weeks there.

In June 1940 the successful Romanian agronomic career was abruptly cut short. My father was at military trainings in Tulce, near the unexpectedly formed new border with the USSR. The commander of the regiment for a given bribe gave the Jewish sergeant a firing note. I do not have details of how the father met his first wife to cross the border, and how they crossed it. Obviously – on foot, on the bridge over Prut, in Reni. Further, the father turned out to be a German spy (!!!) in Balti. Naturally, in the NKVD. Naturally, not knowing a word in Russian. He spent a couple of interesting weeks there.

My father was lucky. In Balti there was a seed-growing station, the chief was sent, but there was no agronomist. How the station commander learned from the NKVD chief that there was a Jew in the cellar, a refugee from Romania and a German spy is a mystery. In short, my father faced a choice: either – Siberia, or – the acceptance of Soviet citizenship and work at the seed-growing station. My father chose the second.

Once I was three years old, his good friend Boris Goldshmidt came to my father on a summer evening. I, a three-year-old, wanted to show myself at the best in front of the guest – they sat on the porch and talked. I took a wooden, similar to an inverted bench, stand for photographs, turned it over, and began to demonstrate that I could sit on it – and not fall. For many years later, there was a picture of a nice gray-haired man with a university rhombic on his lapel in it. Only at the end of my father’s life did I think of asking who it was. “This is the person who saved my life,” the father replied. “This is Skvirenko, the director of the Balti Seed Station…”

Michael Brunya, Chisinau, Moldova