It was one of his favorite stories. My grandfather often recalled it and while telling, he could never refrain from crying.

It was in Breslau, now Wroclaw, just a few days after the victory. His unit was detained in this city, on the border of Germany and Poland. One day he was urgently called to commander.

…Somewhere in the suburbs, he was informed, there are catacombs. The leadership learned that Jews, freed from the nearest concentration camp, were hiding there and some of the partisans seemed to have joined them. They did not want to communicate: either they did not trust, and were afraid, or they simply did not understand what they wanted from them. They were addressed in Russian, in German, and in Polish with no reaction. Grandfather was asked to address them somehow differently, in his own way.

The entrance to the catacombs was blocked by timbers and tightly hammered from the inside. The soldiers unsuccessfully tried to move the wood.

So, what can you do, blow it up in the end?

Grandfather began his conversation in Yiddish, he tried to shout over the stone, wood and emptiness – maybe, those hiding in the depths of these labyrinths could settle somewhere very deep and simply not hear the voices.

He shouted as loudly as he had never before, persuading to go upstairs, assured that they would help, dress, feed them, and no one would never offend them.

When it became clear that the conversation was useless, he decided to sing. He never sang: neither before nor after, he had neither voice nor ear for music, and then he remembered a song, some kind of a lullaby, one of those that his mother sang to him and his brothers.

And … A miracle! A few minutes later the timbers moved from inside, and soon one after another, people began to go out – thin, dirty, tortured, but happy. There were a lot of them, about two hundred, and exactly on that day, at that hour, when an unknown Jewish soldier sang a lullaby for them upstairs, a chuppah was celebrated in the catacombs, and one of the two hundred, who better knew the tradition, blessed a young couple…

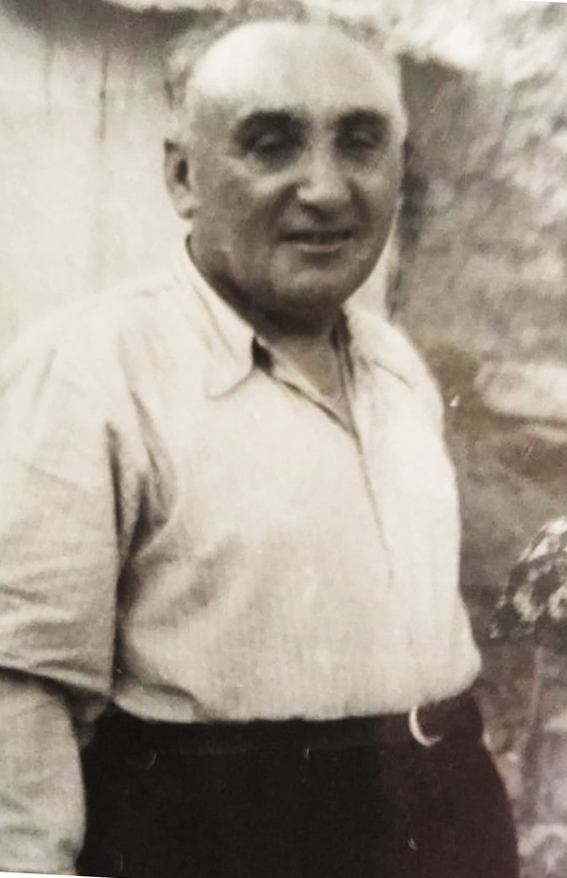

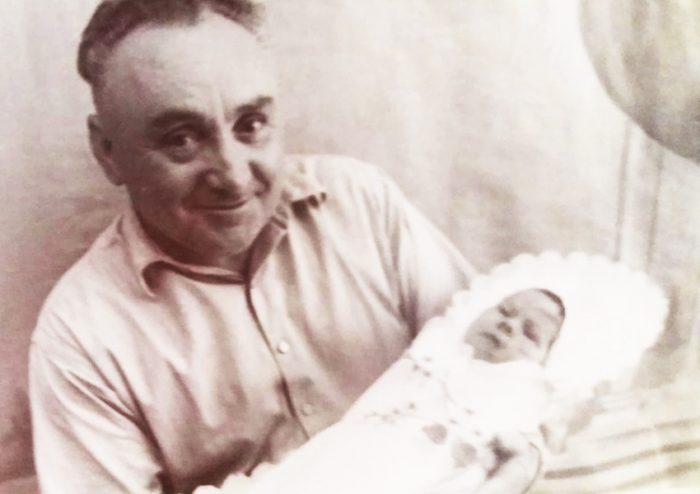

About the hero of the story.

Near the picturesque banks of the Dniester River, there stays Lunga – now known as a part of the town of Dubasari. Lunga settlement for many years was just a single row of houses along the river. Probably, by the beginning of the last century, almost half of the population of Dubasari was Jewish. (https://eleven.co.il/diaspora/communities/11483/)

On December 15, 1902, Efim was born in the family of Gedaliah Lichtgolts. He was the eldest from those sons who had survived. Gedaliah had a sleigh and a cart, and he carried people and cargo. He did not earn enough money, and the family often went hungry. Efim had to quite early think about how to help his parents. However, in Lunga it was not difficult – most of the population of the town was engaged in agriculture, and there was enough work, especially on the tobacco plantations. Efim, and his younger brothers, were engaged in bringing water to the plantings in buckets from the river.

In the winter of 1911, while crossing a frozen river, Gedaliah’s sleigh fell under the ice; he was so wet and frozen that seriously fell ill and soon died. Since then elders had to care for the wellbeing of the family.

Lunga acquired a sad fame in the Jewish history of Bessarabia! In February 1903, murder of a Christian boy took place here, and became the reason for the blood libel. In April 1903, inspired by the slanderous fabrications of the newspaper Bessarabets, the plebs of the capital rose to the pogrom.

Although in June 1903, the boy’s uncle confessed that it was his crime, the genie was already released from the bottle.

In 1903 and 1905 in the town of Lunga, there were several attempts of their own pogroms – opposed by the Jewish population, who organized self-defense squads.

During 1918-1920, when Efim and his brothers reached adolescence, Petliura’s gangs were operating in the town, and a White Guard regiment known for its brutal attitude towards the Jewish population was placed in the settlement. Self-defense experience, inherited from the older generation proved to be useful. It had, however, to be developed and strengthened.

These were the realities of Efim Lichtgolts’s childhood and youth in a very poor Jewish family who lived in a place where constant self-defense became the norm of life, later for obvious reasons it went through the Komsomol, and then the Red Army.

After the civil war, as a young soldier, Efim served in Kiev. The story of his meeting with his future wife – a very young girl Rosa – is also interesting.

Rosa was to sail off to America in a few days. She had a rich but a rather old groom. A bag of plums played a decisive role.

The young soldier Efim bought some plums. Passing across the park, he noticed a crying girl on a bench, went up to her, and treated. Eating the plums, Rosa told the brave guy all her sad story. The need to save the girl became apparent. Rosa did not returned home. A day later, they entered into a civil marriage and left together following the army.

Efim took part in the World War II, from Moscow to Berlin, was wounded. After the war, he found himself with his family in Orhei, where he worked for many years in a financial department.

I remember his office, smelled of crayons and blotting paper. It was a nice and peaceful time. To a certain extent, this was also his merit as well. Efim has three granddaughters and four great-grandchildren. Every year on December 15, candles are lit in front of his portrait in Stuttgart and Netanya – they remember, and I really want to believe that the memory will be preserved for a long time, because our parents are alive as long as the memory of them is alive, as Rabbi Yosef said: “All this lives in me”.

Milana Gilitschenski. Stuttgart. Germany