In the hot July days of 1941, a tragedy occurred in the ordinary Moldovan village of Pepen. One of many that happened to the Jews in those terrible years.

From the memoirs of A. Vulpe-Pepenyanu:

In the early morning of July 13, 1941, the Germans entered the village. After lunch a group of gendarmes appeared, headed by sergeant-major Ion Bordei. In the center of the village, filled with people, he announced that the reservists and pre-conscripts must come at the gendarmerie post.

After a while, armed, they emerged from there in groups, each led by a gendarme and began to drive the Jews out of their homes. We saw how the Jewish families, with their household belongings in their hands, went to the town hall building under escort. Among them were my classmates. Silently they waved to me. Nobody suspected that this was the last goodbye.

In the evening, when the sun hid behind the hill, I returned home, worried and frightened by what I had experienced. Everything was as usual. Mom milked a cow and boiled milk, my father threw dry corn on the fire. I told about what I saw. My father mumbled something, I just sorted out: “So is in the war.” Mom crossed herself and, raising her eyes to the sky, said: “Save, Lord, our village from the military disasters.”

From the memoirs of A. Zaslavsky:

In one day old people, children, pregnant women – more than 300 Jews, not only local Jews, but also refugees from Balti, Telenesti and other towns were imprisoned in the premises of the city hall. They were closed in four rooms with barred windows. Nobody was let in. Four days of July heat without water and food, humiliated, in fear and horror – it’s hard to even imagine what these people experienced.

In one day old people, children, pregnant women – more than 300 Jews, not only local Jews, but also refugees from Balti, Telenesti and other towns were imprisoned in the premises of the city hall. They were closed in four rooms with barred windows. Nobody was let in. Four days of July heat without water and food, humiliated, in fear and horror – it’s hard to even imagine what these people experienced.

From the memoirs of A. Zaslavsky:

Brothers David and Abraham Klinger before the war were well acquainted with the former prefect Kotelea and counted with his help to ease the situation of the prisoners. In the morning they asked I. Bordei for a cart to go to Mr. Kotelea in Balti. Brothers got permission for this trip together with their families. On a cart accompanied by two gendarmes they left in the direction of Balti. Three kilometers from Pepen, the gendarmes jumped from the cart and shot everyone, not sparing the eighty-year-old mother of the Klingers. Only twelve-year-old son of David managed to hide in a cornfield. The gendarmes had accomplices. Passing by two residents of Romanovka helped to complete the black business for part of the Klingers’ property. I deliberately do not mention the names of them and some other performers of the bloody slaughter. They are no longer alive, and their descendants, in my opinion, should not bear moral responsibility for the atrocities of grandfathers and fathers.

From the memoirs of A. Vulpe-Pepenyanu:

… In the evening, from the village of Razelai, there were shots. The commander of the gendarmerie raised the alarm: “The village is in danger, together with part of the Red Army, Kikes from Kaprieshty are coming to release the arrested and set fire to the village.”

… In the evening, from the village of Razelai, there were shots. The commander of the gendarmerie raised the alarm: “The village is in danger, together with part of the Red Army, Kikes from Kaprieshty are coming to release the arrested and set fire to the village.”

Part of the residents went out to defend the village, part left with I. Bordei in the village.

By the order of the commander, the pre-conscripts were given rifles and cartridges; they were taught how to breech them. It was necessary to keep the rifles ready and on command to give them to the gendarmes. The doors of the room where the Jews were held were locked. Guards stood at the windows. For them also it was a surprise when Bordei threw a grenade into the room where the men were held. The gendarmes started shooting at the windows. Of all those who were there, only Zosya Talpalatskaya and her cousin Moshka, my classmate, remained alive.

From the memoirs of A. Zaslavsky:

A few people survived. Two of them: my wife Sophia Zaslavskaya and her cousin Mikhail Talpalatski were locked in the premises of the city hall. When shooting began wounded Srul Talpalatsky, father of Sophia, jumped out of the window with his daughter and nephew. They managed to escape. Having agreed with the children to meet behind the village, he went to the house to take the essentials. From the pain he lost consciousness on the way. Woke up, he called for help. On the voice a neighbor came with a hoe in his hands and … “helped”. Just a few days ago they talked peacefully…

After midnight, it was quiet. To the place of reprisal they drove up several dozen of carts, to which the corpses were fallen. They were taken out of the village and dumped in stone mines. Eyewitnesses recalled the thirteen-year-old daughter of the teacher Meer Turchin. She saw how her mother was killed, and she herself, wounded and unconscious, was thrown on a cart over dead bodies. In delirium, she prayed only for a drop of water, but no one dared to approach. The girl was thrown to the bottom of the pit, pelted with corpses. Sergei Grosu, who took part in this terrible tragedy, later told me that when Ion Bordei found out that there were alive in the pile of bodies, he ordered “checking” the corpses. Before loading, one of the gendarmes pierced the head or chest with a bayonet. In the morning, several frightened women and draftees were brought and forced to wash this terrible place. They were haunted for a long time by the horror of what they saw. The gutter was full of blood. All day long the village spent in a daze from the experienced.

A few days later a commission was established, consisting of mayor, notary, the head of the tax department, commander of the gendarmerie post and a retired officer of the Romanian army. They were accompanied by volunteers from those who took part in the massacre. The commission was to requisition the property of the Jews. They stopped at every house. Valuables were immersed in the carts, then the mayor called the name of the distinguished, awarded the right to take the rest. And they, who, being proud, who, ashamed, carried away the remaining belongings from houses that had recently been full of life. And those who helped the gendarmes, who participated in the murder, enjoyed special privileges. The commander of the post, I. Bordei, respectfully called them “the heroes of the nation”; they were given the best land allotments for free.

From the memoirs of A. Vulpe-Pepenyanu:

I want to return to the story of David Klinger’s son, who has escaped from the massacre, and hid in corn. The exhausted and frightened boy wandered through the fields and on the third day went out to a sheepfold. Shepherds fed him, dried his clothes. He spent the whole Saturday with them. But a rumor spread in the village that a Jewish boy appeared on the sheepfold. He was followed by a gendarme who brought the child to the village. The people silently looked at the boy in short pants, who looked around and greeted his acquaintances. We, his peers, tried to talk to him, but the gendarme drove us away. At his uncle Avrum’s house, he stopped and asked permission to take something from the things. The gendarme forbad and took him in a court yard of a post. There he asked I. Bordei what to do with the boy, and received the answer: “The same as with the rest.” The child seemed to be allowed to turn down the path to his uncle’s house. The gendarme followed him. Two shots followed…

I want to return to the story of David Klinger’s son, who has escaped from the massacre, and hid in corn. The exhausted and frightened boy wandered through the fields and on the third day went out to a sheepfold. Shepherds fed him, dried his clothes. He spent the whole Saturday with them. But a rumor spread in the village that a Jewish boy appeared on the sheepfold. He was followed by a gendarme who brought the child to the village. The people silently looked at the boy in short pants, who looked around and greeted his acquaintances. We, his peers, tried to talk to him, but the gendarme drove us away. At his uncle Avrum’s house, he stopped and asked permission to take something from the things. The gendarme forbad and took him in a court yard of a post. There he asked I. Bordei what to do with the boy, and received the answer: “The same as with the rest.” The child seemed to be allowed to turn down the path to his uncle’s house. The gendarme followed him. Two shots followed…

From the memoirs of A. Zaslavsky:

Thirty years after the tragedy, in 1971, a village gathering decided to erect a monument on the site of a house where 326 Jews were killed in July 1941. The collective farm management ordered a sculpture in Lviv. Two months later it was brought to Pepeny, where on July 10 they were to open the monument. But the initiative seemed suspicious to the district leaders. Since then, what was thought of as a monument to innocently murdered people, and could become not only a reminder of the tragedy, but also a warning for the future, is lying on the collective farm stock.

Now, while those who have seen this horror are still alive, we simply have to put this monument in the place of their execution or where they are buried. Children and grandchildren will not forgive us a short memory.

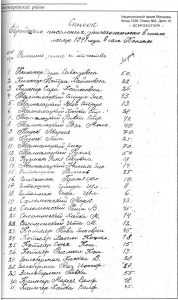

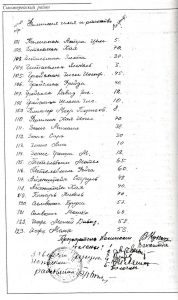

Village of Pepen (Pepeny) of the Singerei district. According to the 1930 census, there were 216 Jews living in the commune of Pepeny (it included the villages of Pepeny, Prepelitsa, Balasheshty, Slavyanka, Razalei). Only Pepeny Jewish community consisted of twenty-nine families. Among the Jews there were tailors, shoemakers, furriers, and dyers. Merchants were the most prosperous.

Aaron Zaslavsky. A native of Pepen, he put a lot of effort into development of the local collective farm. For this he was awarded the highest Soviet award of the Order of Lenin. Since 1977 and before his passing away Aaron Zaslavsky headed the village administration.

His wife, Sofya Talpalatskaya, rescued together with her cousin Mikhail by the Zaslavsky family, was in charge of the post office for 35 years. After the death of her husband she left for the USA to her children and grandchildren. Memories were written in 1991 and found in the archives of the historian I. Golovaty.

Andrei Vulpe-Pepenyanu:

Was born and raised in Pepen. He graduated from the pedagogical college and the historical faculty of the university. He worked as a teacher in his native village. Memories were recorded in November 1999.

Monument to the victims of the Holocaust in the village of Pepeny. In 1971, according to the decision of the rural assembly, a monument was ordered. For more than 30 years, the sculpture has lain in a warehouse without obtaining permission to install from the Soviet authorities. Thanks to the financial assistance of Dr. Steve Makler and his family from the city of Greensboro (North Carolina, USA) and with the participation of the Association of Jewish Organizations in Balti (Chairman Lev Bondar) in 2004 the monument was opened.

Monument to the victims of the Holocaust in the village of Pepeny. In 1971, according to the decision of the rural assembly, a monument was ordered. For more than 30 years, the sculpture has lain in a warehouse without obtaining permission to install from the Soviet authorities. Thanks to the financial assistance of Dr. Steve Makler and his family from the city of Greensboro (North Carolina, USA) and with the participation of the Association of Jewish Organizations in Balti (Chairman Lev Bondar) in 2004 the monument was opened.

Many details of the Pepeny tragedy will never become known, the victims will not speak, and the last witnesses pass away. But also from what we know, it breathes as a primitive horror, although the executors of the atrocities were, it seems ordinary people. Not those foreigners who speak German, but those who lived side by side with the victims. The most terrible, as many Jews who survived in the Holocaust, stressed the tremendous shock that neighbors, colleagues, friends, those with whom they drank wine, laughed at one joke, wept about one grief killed them.

We do not know and will never know what the survivors of the tragedy felt like, how they walked through these streets, how they lived, breathed the same air … And why they returned.

Pepeny is only one name on a scary map, where the places of mass extermination of Jews are marked: Edinets, Marculesti, Vertyuzhany, Riscani, Dubossary, Rezina, Radoya…

In preparing the material were used:

“No prescription, no oblivion.” 2004 Chisinau, Chisinau Jewish Community Center. Editor Dorina Schlaen

“The Holocaust in Moldova. Facts, Facts Only,” 2007 Chisinau. Compiled by Mikhail Becker

Project ” The Holocaust unhealed wounds” with support Yad Vashem- the Holocaust Martyrs’ and Heroes’ Remembrance Authority and the Genrsis Philanthropy Group.